All previous chapters are posted in the Bartle Clunes archive for you.

The newly formed family of four were seated around the kitchen table having coffee. Maggie was under the table, his chin on Ayla's knee, eyes closed. She rubbed his ears. The chicken stew simmered on the stove, a rhubarb pie waited on the counter. The kitchen was warm, the windows steamed up. Wet coats and jackets hung by the kitchen door. The room had a cozy fragrance of onions, herbs and damp wool.

Bartle had carried Ayla's two small trunks into the blue-painted bedroom and put them on the floor. Louvina took Ayla's hand and followed him in. “This is my room?” Ayla asked, turning around two times. “I have never had a room anything like this. You have made it so beautiful, I don’t know what to say.

“We hope you like it, Ayla,” said Louvina. “Your father painted it for you, and he put a lock on the door for you, too. See here? He thought maybe you would want your privacy. I’ll help you find places for your things in the morning, if you like,” she offered, “and we’ll talk about what else you might need in order to feel at home here.” Ayla hugged her shyly, and thanked her again.

Later, after supper was cleared away, Ayla put on her jacket, saying she would just step out into the yard to look around and get some air for a few minutes. Maggie tagged along. The cold breeze made her eyes water. The sky was unusually clear, Venus brightly showing off in its descent to the southwest. The snow had nearly melted already, and there was no sign of more for now.

Bartle and Louvina stood at the kitchen window watching Ayla throw a stick for the dog in the waning light. “Well, what do you think?” he asked, putting his arm around Louvina’s shoulders and pulling her close.

She shook her head and said, “Well ... I think that dog doesn’t know overmuch about fetching a stick.”

Bartle laughed. “Yes, that is the sorry truth! But I mean Ayla — what do you think about her?”

“I think she is a strong, smart, beautiful young woman, one to be proud of. And... I think we need to feed her more than she’s used to and get some muscle on her.”

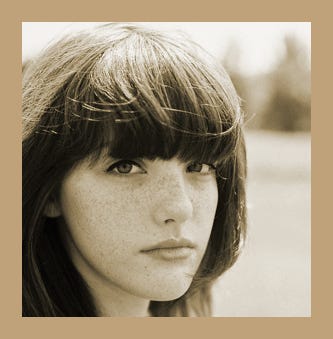

Bartle watched his daughter play with the dog in the near dark. She was angular and wiry like he was. Her hair was fine like his, but darker. It fell plain and straight to her shoulders. Her jaw was square and determined. In her rumpled trousers and plaid shirt, she reminded Bartle of Louvina, saving that Ayla’s step was quick and light, like a deer, and Louvina’s was solid and full of purpose.

Ayla came back in with a shiver, shaking her head. “That dog does not appear to know much about fetching a stick. And why is he called Maggie anyway?” Louvina laughed and told her that was a long story.

They spent the early evening chatting about her new family acquaintances in Wyoming and her train ride. All three were too tired for serious talk. They listened to “The Whistler” on the radio and by 9:30 they all decided that the day was done.

“Tomorrow afternoon,” said Louvina, “I’ll go down to the big grocery in Placerville and pick up what we need for our Thanksgiving dinner. You could come along, Ayla, if you want to help me shop or you could have a look around the town. Or you could stay here at home and settle in. Whatever you like.”

Bartle said he would run over to Riles Crossing around mid-day to make sure Lonnie Riles and his father were still coming to dinner on Thursday. He and Louvina had agreed that those two men could profit from a little family on the holiday, as Mrs. Riles had died earlier this year. “You could ride over there with me, too, Ayla. We will figure it out in the morning,” he said, and they left it at that.

Lying in their bed, Bartle recounted to Louvina his daughter’s story in detail, as she had told it to him on the drive home.

“That girl’s life will be different here,” said Louvina. She has spent a good deal of time alone it seems and she is used to fending for herself. I hope the close companionship she finds with us is not more than she can abide. We may have to step back a while, give her some room to breathe.” She rolled over, putting her back to his chest.

“Yes, we will,” he agreed. He gathered his wife in and bent his knees behind hers, like two spoons in a drawer, and Bartle knew he was the happiest man alive.

Before climbing into her bed, Ayla explored her new room. She ran a hand over the patchwork quilt, the pillows, the small ceramic parrot lamp, the embroidered dresser scarf. She peeked inside the polished wardrobe and saw it was empty. The small bookcase was full of old books. She picked up two of them - a shabby illustrated copy of Ivanhoe, which she had read years before, and a history of the Vikings in Britain, which she had not. “Oh goody,” she whispered to Maggie, who was watching her. She went to the window and pulled aside the curtain. She studied the dark stand of tall bay laurels silhouetted in the moonlight.

Ayla rose at first light. She’d had a night of lightly troubled sleep, disorderly dreams. Putting on a shabby plaid robe over her flannel nightgown, she quietly opened one of her small trunks. She hung her shirts on wire hangers in the wardrobe and folded underclothes and trousers into the drawers. She had very few garments for a 17-year-old girl. In the bottom of the wardrobe, she set her penny loafers and a pair of old cowboy boots with dark green inlays on the shins.

The contents of her trunks, for the most part, were her accumulated treasure, her note books and pencil boxes, a portfolio constructed from a cut cardboard box and tape. There were small valuables tucked away in a tin box, a paper box, an egg carton, a drawstring bag, some small fruit jars. The smaller trunk held a battered, faded rag doll, three wooden spinning tops, and books. A lot of books.

Louvina tip-toed out at sun-up to start her day. She stopped by Ayla's door which stood half open, and tapped lightly. “Morning, Ayla. You okay in there?” Ayla peeked out and nodded. “My, you are an early riser. Did you sleep well?”

“Yes, thank you, I did. Maggie slept in here for a while. I hope that was okay. I didn’t let him on the bed, but he did try a few times.”

“Well, you’ll find that dog often has aspirations that don’t work out for him. But he is a good boy, and he seems to have taken a shine to you. What do you say we go out and turn on the heat and make us some coffee before your dad gets up.”

Bartle went outside right after his oatmeal breakfast to tinker with the wiring of the head lights of Louvina’s truck, which were on the blink again. There was no end to the repairs on it, and he feared he would be obliged to work on that vehicle until he was dead.

Louvina spent the entire morning with Ayla in her room, fascinated by the things the girl had brought along with her to her new home. Ayla was pleased to show them to her, as if no one had ever been interested in her things before, or, indeed, interested in her for that matter.

She was a collector with wide and varied interests. In a cigar box was a small quantity of arrow heads that she had dug up. Mounted on paper, she had single bird feathers, neatly identified. She then opened an egg carton.

“These are the minerals I have found so far,” she told Louvina. Each one was carefully labeled: opal, beryl, garnet, crystallized copper, cinnabar, malachite, pyrite. In a small tobacco tin there were tiny desiccated bones that she described as “field mouse, sparrow and bat.” Several little glass jars held bits of herbs she had gathered. They were hand-labeled in green ink as yarrow, ginger root, willow bark, spearmint, fennel seed, wintergreen, licorice root, sarsaparilla bark.

Louvina saw that the girl had a well-ordered, methodical mind like her father’s, and she told her so. Most interesting of all to her were Ayla’s notebooks and her makeshift portfolio, full of sketches from nature. She had made drawings of bird’s wings and feet, of plants and their root systems, of small rodents and insects. One notebook was all wildflowers done in charcoal and pencil. They were meticulous, nearly photographic. “Will you take these drawings out to the kitchen and show them to your father, Ayla?” she asked. “I know for a fact he would love to see them.”

Bartle came in and scrubbed the grime from his hands. He and Ayla sat at the table for about an hour, looking though the drawings. Her father was enthralled and found himself hoping he had something to do with her natural, unschooled talent.

“These are beautifully drawn, Ayla,” he said, “and very smart. You have a good eye for fine detail. I think you could make your living as a natural history illustrator. You should be very proud of this work.” Then, as an afterthought, “You know, I do a bit of drawing myself. Later today, I will show you some of my work to see what you think.”

Like father, like daughter.