Chapters are listed in order in the Bartle Clunes archive. Click here.

If you are new, please start here: Introduction to Bartle Clunes .

El Dorado County 1951

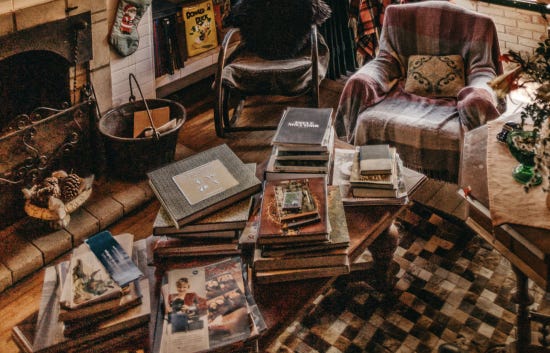

Eli Flounder picked up his battered suitcase and wrestled it clumsily up the steps, half-dragging it through the front door. He looked around at the place Eizer called home. The floors were not clean. The dust on the tabletops was so thick it rose up into the air when you walked by and then settled back down. Cobwebs hung from the light fixtures, an accumulation of years, no doubt. The curtains looked as if they had not been washed since 1925, and one roller shade was ripped half off. There were stacks of books on every horizontal surface – on tabletops, on chairs, like a library gone to hell. The couch had become a repository for so much flotsam, there was no longer a place to sit. The air in the room was redolent of fried onions, cabbage, liniment, dirty socks, and … poultry.

The boy followed the old man into the kitchen. Two chickens were pecking around on the drainboard. Eizer yelled and flapped the dishcloth at them. They squawked and flew out the open window over the sink. He lit the burner on the greasy stove and put a lime-crusted tea kettle on to boil. Pushing a pile of unwashed dishes, pots, and potato peelings aside, he made a place on the counter to work. “You like peanut butter? I'll make us a sandwich. And we got plenty of milk, God knows.” He found a half-empty jar of Skippy's in the cupboard and said, “You make us a place at the table there, son, and we'll eat.”

Eli gathered up a stack of rubble from the table and arranged it carefully on the chair in the corner. He brushed off the oilcloth in front of him, scattering crumbs and other questionable substances onto the floor. Climbing up on a chair, he waited quietly, looking around, feet dangling. Eizer brought him a plate with a sandwich oozing thin peach jam that was made by a neighbor. He added a slightly wrinkled apple and a tall glass of milk. The smear of dried egg yolk on the rim of the plate was just decoration, left over from yesterday's breakfast. “You eat,” he said. He made a cup of Sanka and a sandwich for himself and joined the boy at the table. “That good?” he asked.

“Yeth, thir,” Eli answered through a mouthful of goo. “Thank you,” he added, remembering his manners. Jam ran out of the sandwich between his little fingers, and down toward his wrist. He tried to lick it off. Eizer handed him a rag. A minute or so later, Eli looked around him and said thoughtfully, “This house is a mess.” It was not a criticism, really, just an observation.

“Well... yes it is,” Eizer agreed gruffly. “There's no excuse for it.”

After they ate and Eli had washed his sticky hands and face, he remembered an envelope he needed to give to Eizer, and took it out of his pants pocket. “I forgot,” he said. “My mama wanted me to give you this. It's a note.” Eizer opened the wrinkled envelope and read:

Dear Eizer

I am sorry, I had to leave fast. I am in bad trouble and I cannot keep this boy anymore. You have to take him. He is a good boy. I love him, but he is not safe with me now. I will come back for him when if I can.

Merlene

Eizer read the note two more times, thinking he must have misunderstood something, but he hadn't. He stared out the window, blinked at the boy. What was he supposed to do now? He sat and waited for inspiration. A minute passed silently.

“Mr. Griggs? Sir? What is it? What does the note say?”

Eizer snapped to and quickly stuffed the note in his pocket. “Ah ... your mama says she will come back for you just as soon as she can and that I am to take good care of you,” he said, telling the truth. “You are to stay here and you are not to worry. Now … let’s us go out back and get that cow milked and bring in the eggs.” Eli jumped down from the chair and followed Eizer Griggs out into the yard.

The area between the house and the barn looked like the scene of a train wreck, an explosion of some sort. Debris everywhere. To the left, old tires, rusty springs, scrap lumber, a defunct water heater, the back end of a pickup truck. To the right, a broken trellis, battered discolored sheets of corrugated tin, various mysterious farming implements, a roll of chicken wire.

The cow was out in the sun in a large enclosure. Eizer tied her lead to the fence got the three-legged stool and a bucket and sat down beside her. Eli squatted down to watch. “What are you doing under there, Mr. Griggs?” he asked.

“Why, I am milking this cow.” He patted Rosie affectionately on her flank. “This is where the milk for your breakfast comes from. Did you not know that?”

“No sir, I didn't.” He watched, fascinated, for a minute as the bucket filled with foamy milk. “Mr. Griggs, does it have orange juice in there too?”

“No, it doesn't have orange juice,” said Eizer. “Be nice if it did, though. Be right handy. Now you go over there to those five boxes, take that old basket with you. See if you can find us some eggs. Be careful now, they break easy.”

“But … there's chickens in there, sir.”

“Pay them no mind. You just reach under, see what you can find.”

The boy approached the chickens warily. He was getting a sideways, beady stare from a large white hen that looked as if she’d as soon peck his eyes out as not. He said, “Excuse me,” to her and slid his little hand under the warm, sturdy Leghorn. To his delight, he found a fine large specimen and placed it gently in the basket.

“See there?” said Eizer. “Easy! That will be your job every day now. You will be the egg man here.” Eli thought about that. I'm the egg man here.

Later, Eizer cleared off the bed for Eli in the room he himself had slept in as a boy, a room as haphazard as the other five rooms in the house. He put all the books on the dresser, made up the bed with worn but relatively clean sheets. The blankets were somewhat the worse for wear, but he took them outside and gave them a good shake to get rid of most of the dust and a spider or two.

“Good,” he said, looking down at Eli. “That'll do. Now let's see what you have brought here in your suitcase so we know what we have to work with.” Eizer, for some inexplicable reason, did not resist the sudden obligation of this child. Rather, he seemed to welcome it, taking it on with alacrity and grace. Somewhere inside him he was making room for this little boy.

Eli opened his Sears & Roebuck suitcase and pulled out a pair of worn-out jeans, two cotton shirts, a sad looking denim jacket, various mis-matched socks, and pajamas. Merlene apparently overlooked the underwear, but she had put in a book, The Tin Man of Oz, four metal Matchbox cars and a stack of baseball cards with a rubber band around them. In a rolled up paper sack he found a tooth brush and a comb. There was a large torn manila envelope in the bottom of the suitcase, in which Eizer found the boy's birth certificate, some records of immunizations and his school history, which confirmed his suspicion that Eli's mother would not be returning any time soon, if ever.

“Well, looks like we are going to need a few things. We'll go into town tomorrow and take care of it. We will make a good adventure of it.”

Eizer prepared a dinner of Spam fried up with turnip greens. Eli helped him whip up a cornbread from a boxed mix. It‘s a pretty good dinner, thought the boy. The corn bread was very dry and he drank two glasses of milk to get it down, which may have been intentional on Eizer's part. After dinner, Eizer added the dirty dishes, bowls, and skillet to the wreckage on the drainboard and said, “We’d better get to cleaning up this kitchen tomorrow, don't you think?”

“Yes, sir, I do,” Eli agreed.

Eizer Griggs, not knowing exactly what to do next for this boy, began to hear an echo of his own father's voice from so long ago, telling him …you get in there and take a bath and brush your teeth now, son. And remember to scrub behind your ears and wash your hair. He turned to Eli, and, using what he thought was a tone of benign authority, said, “You get in there and take a bath and brush your teeth now, son. And remember to scrub behind your ears and wash your hair.” He ran the bathwater and was pleased to see the young man emerge from the bathroom half an hour later in his faded pajamas, damp, and shining like a silver coat button.

“You look mighty fine,” he said to the boy. “Good work.”

The boy replied, “Maybe we should get to cleaning that bathroom, too, sir.”

“Right you are,” Eizer agreed.

Food, bath, teeth brushed, now what? How would he entertain this child? He rummaged around in the bedroom closet, and brought out a dusty box of old children's books. “You look through these, son. Find one that looks interesting and I'll read it to you if you want.”

“I can read,” said Eli. “I am six and a half.”

“Well that is just fine. Then you shall read to me, and we will try to learn something useful.

Later that evening, before retiring to his own disorderly bedroom, Eizer peeked in at young Mr. Flounder to make sure he was all right. The light from the bare bulb in the hall shone dimly into his bedroom. He stood there in the doorway listening, watching the boy sleep, and was taken by a feeling of responsibility that was utterly new to him. He had someone to tend to, a human being who needed him for the first time in his life.

Eizer had been nearly the same age as this boy when his mother had disappeared. He remembered the confusion, the sadness, the overwhelming sense of loss and of somehow feeling to blame for it, as if he had done something wrong that drove her away. As he lay in the turmoil that was his bed that night, Eizer found his first clear direction as to how to care for this boy: No matter what, he would never let him feel unwanted.

I think Elizer needed Eli as much as Eli needed Elizer.

So many orphans back then....