She was sitting at a table in Café L’Onda with a strange man. He was strange in the sense that they had just met that morning on the train from Milan. They had talked together, tentatively, as people do. He might have been the other kind of strange as well. He had a slow, hesitant way of speaking, a way of tilting his head as he listened. He looked at her intently, as if trying to visually process her words. His name was Julian.

And now they had run into each other again, in this small lakeside café. He recognized her as she came in, and waved to her to join him. They were waiting for their meal now and sharing the calm, gray view of Lake Como framed in the large windows.

“Have you been following my suggestion this morning,” he asked, “to look carefully at the small details?”

“I have, actually.”

“Everything appears to be in disguise today, doesn’t it?”

“How so?”

“Well, for example, the lake. Look how it shines, the smooth, deep, purple-black of an aubergine. Do you see it?”

“Yes, I see it.”

“And the mountain? What do you see there?”

“The mountain. Well...”

“Take your time. Look carefully.”

“I see the muzzle of an old dog, black with gray-white speckles of snow.”

“Yes, good,” he nodded. “You’ll not forget that. And the bare trees along the shore just there?”

“They are … brooms sticking up out of the earth, about to sweep the clouds from the sky.”

“You see? Exactly so.” He touched her hand lightly, his fingers were warm. “You don’t need a camera. And what about the colors of the plastered walls?” he asked.

“You tell me, Julian.”

“I see that the bright lemon and orange colors of the walls are muted in this light fog, softened to peaches and apricots … with cream.”

“Oh, yes,” she smiled.

The waiter brought their food. “Buon appetito, madam.” She liked it that the waiter called her madam. No one ever called her madam at home.

Bowls of creamy polenta with a simple rustic sauce and cheese. A small platter of prosciutto with melon. Crusty bread and butter in a red basket. A bottle of light Bardolino.

“This is perfect,” she said. “So delicious. It could easily be my final request if I were facing execution.”

“D’accordo,” Julian said.

The meal was wholesome and plain. It satisfied their hunger, filled their spirits, though other unnamed hungers, perhaps, remained unmet. They were silent for a time, absorbed in their meal. He filled her glass again and called for another bottle.

The train to Como had departed from the Cadorna station in the center of Milan early this morning. The old railway line was separate from the high speed trains that screech into and glide out of the Central Station. The Milano Nord is a short, direct line, Lake Como its only destination, really.

The fancy Art Deco ironwork of the car delighted her. From a bygone era, it decorated the seat backs and formed the overhead rails. The interior was highly polished wood, the seats, varnished and slatted like park benches. They were narrow and not at all comfortable, but charming in their way. At that morning hour, the train wasn’t crowded, there were plenty of open seats, but he had come down the aisle and stopped directly in front of her.

“Buon giorno. Do you mind if I sit here?”

“Not at all,” she said, and continued studying her guide book.

He threw down his daypack and sat down across from her. “Going up for a boat ride, are you?”

“Excuse me?” She noticed his eyes were the dark brown of chestnuts, his face, rough and unshaven. She imagined touching his cheek.

“I was wondering if you were going up to Como for a boat ride.”

“Yes, I suppose I am. Just a day out, really. I am looking for some clean air. Milan is killing me. You know how it is.” Her book slid off her lap onto the floor. He bent to pick it up for her, accidentally touching her bare knee.

“I understand,” he said. “I escape north as often as I can. The city air is oppressive. It can make you a little crazy.”

“Yes. That’s it.”

“You know, there is a very fast hydrofoil ferry – the aliscafo, that goes all the way to the north end of the lake. It skims across the top of the water like a flying fish. A remarkable ride if you have never done it.” His English, though slow, was impeccable, lightly accented — his voice, oddly polite. “But if it is your first time in Como, I recommend one of the old steamers – The Iris, perhaps, which travels only about thirty minutes north and then crosses the lake and comes back. You can go up and back without getting off, just for the ride, or you can get off in any of the small villages for a little explore. The steamers, they run like buses, you can always jump on the next one.”

“That sounds lovely. Thank you.” He took off his jacket and hung it by the collar on the window hook. She continued reading.

“My name is Julian, by the way.”

She looked up at him. “I’m Roselyn.”

He reached over and shook her hand, holding on to it maybe just a little too long. She thought his hand felt unusually warm. She imagined her arms around him.

After a moment of awkward silence, she said, “And what will you do at the lake today, Julian?”

“I’m going to make sketches. Capture some colors, some faces.”

“You are an artist.”

“Yes. Maybe. I like to study humans – the behavior of humans, and make drawings.

“Humans. You make it sound like we are not of your species, Julian, when you say humans, as if you were from a different world,” she laughed.

“Yes … I meant to say people. I like to observe — people, landscapes, small objects, just to see what can be found here. I don’t want to miss anything, but I don’t like a camera. I’m recording my experiences in drawings. What do you like to do Roselyn? Do you mind my asking?”

“No, I don’t mind. I write. I am based in Milan for a few months.”

“You write … because you like it or because it’s your work?”

“Yes,” she answered. “Both.”

“I see. A writer. Does being a writer leave you time for … adventures?”

“It does.”

“Do you consider yourself adventurous, then?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Excellent!”

Julian retrieved his small notebook from his pack, she turned back to her book. He watched out the window for a time, and then began to draw Roselyn as she read. He studied her. She didn’t mind. She wondered what it would be like to kiss him.

When the Lake Como station came into view, Julian said, “Here we are, then, end of the line. If you are going directly to the piers, they are just there, across the park.”

“I thought I would take the ride up the hill to Brunate first, just to get a wide view of the area.”

Julian waited, but she didn’t invite him to join her. “Enjoy your day then,” he said. “Oh, and listen, Roselyn, may I make a suggestion?”

“Go ahead.”

“As you look around today, whisper aloud what it is you’re seeing, just softly. I promise you’ll remember it forever if you do that. And pay attention to the small things that are right in front of you. I say this, because we sometimes move too quickly through a new scene and miss so much beauty.”

“Okay, Julian. I’ll try whispering to myself. I will. You have a fine walk,” she said, “and maybe I will run into you on the train back.” She turned and walked toward the east shore.

The cable railway ascended the hillside to the village of Brunate. She looked back over the scene below, and in seven minutes, she stepped out of the tram at the top. “It is gray and damp today, above the forest that surrounds the lake,” she whispered aloud to herself. “The mountains are blurred in the distance. The rich smell of coffee is in the air. The little café and gift shop are open, but quiet. The white plaster of the church is like bleached linen hung on a clothesline.” She wandered over to a small terrace, and looked down upon the city walls of Como, then north to a little scatter of villages and then, far beyond the lake, the western Alps, the Po Valley, the Apennines. She noted that the coffee was very expensive in the café, but she knew she was really paying for the privilege of sitting on their terrace.

Julian had suggested she pay attention to the foreground as well. “I see an orange-striped cat at his bowl with drops of milk on his chin,” she whispered. “Small brown birds under the table pecking at bread crumbs shaken from napkins. The undissolved sugar waits in the bottom of my cup, the best bit saved for last. The cobble stones are concave, well-worn from the century-long passage of feet to the church.” Descending, later, on the tram, she photographed with her eyes the basilica in the main town square below.

On the front deck of The Iris, seated alone, she continued to whisper impressions softly to herself. “The spray stings my face, lightly. The air is clean and smells of fish and algae and water weeds. The thrum of the motor, the gentle rocking back and forth, is like a cradle. I have been in the city for too long.”

In the early afternoon, Roselyn disembarked at the Cernobbio stop on the west side of the lake. She would walk the rest of the way back to Como – an hour’s stroll along the shore. But first, lunch. She found the Café L’Onda, with its three large glass windows facing the lake. There were not that many people there on a Wednesday in February. She immediately saw Julian sitting next to the east window. He looked up and smiled. Cocking his head to one side, he waved and stood up.

“Are you following me then, Roselyn?”

“No, actually I just ...”

He laughed. “You know how Italians feel about eating alone, don’t you? It is a terrible shame! Almost criminal. If they see you at a table reading during a meal, they are sure you have absolutely no friends at all, no family, and they shake their heads in pity. But if you’ll join me, we can save them all the heartache.”

“Well, okay, then. I certainly wouldn’t want to ruin someone’s lunch.”

“Here, please,” he held the chair for her. “Sit. Tell me about your day so far.”

“I can only say that abandoning the madhouse that is Milan was a very good idea. This day at the lake makes me feel as if I have just gotten over the flu or something worse. Oxygen! Apparently it’s an excellent curative. I am sure you feel the same.”

“Yes,” he said. “Yes, I do.”

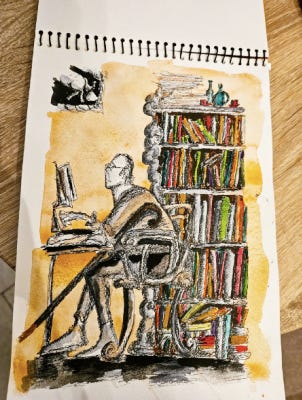

Over a bowl of lemon gelato and coffee, Roselyn asked to see Julian’s sketches. He didn’t protest, he pulled his notebook out of his pack and handed it to her. The drawings were remarkable. They were done in pen and ink with a bright wash of color: a thin bearded man, a man working in a book shop, a young girl with flowers, an insect.

“These are absolutely charming, Julian. What an eye you have! I just love these. What will you do with them?”

“I’ll study them and find their meaning. They’ll help me understand the people here.”

After their meal, Julian and Roselyn began the long walk back together. He offered her his hand.

““Your hands are very warm.”

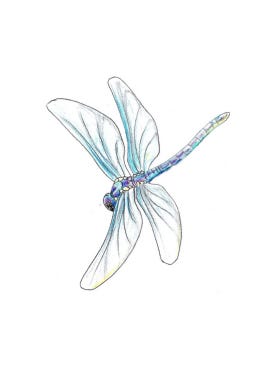

“Yes,” he said. “I saw a dragon-fly today. It was on a headstone in the cemetery. I’d never seen one before. Its four wings were long and clear as glass with tiny veins. And an extraordinary long blue body and head with small black marks. I am glad I didn’t miss it. We don’t have such creatures where I am from.”

She didn’t ask. At the moment it was not important where he was from. He was strange, she decided, but she was curious to know more. She’d been waiting for someone like Julian for a long while, someone a little out of the ordinary. She wondered what it would be like ….

Thanks to Kenneth Mills, writer, painter and photographer on Substack, for generously allowing me to borrow two of his sketches. His excellent publication is DISPATCHES.

Thanks to Jim Cummings for his always welcome editing! Have a look at his publication ALL DAY LONG

Lovely story. Intriguing, sophisticated, elegant. The dialog is sharp and full of personality.

Having read this in draft form without visuals, I must say that the photos are exactly what I envisioned from your scenic descriptions. Beautiful piece Sharron!

I started this story but was interrupted and was happy to return to it. Loved the air of mystery you created here, Sharron. I was expecting a surprise. And my imagination ran with the possible scenarios.

Was Julian blind? No he wasn’t blind.

Was he a ghost? No, ghosts don’t have warm hands.

Would the couple reunite; run into each other again or plan a rendezvous. So many ways to go with this. And where was Julian from? I would have asked.