.

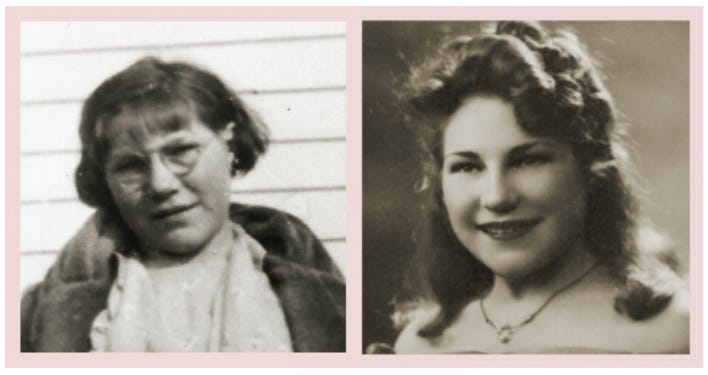

The direct quotes in this story are from a taped interview of my mother, Katy, when she was 75 years old. The tape and transcript of her voice is a priceless treasure to her family

“I was six when I started school. I spoke no English and the teachers made no concessions for me. They never even tried to teach me English. I guess they thought if I sat there long enough I would learn it. And I did, but it kept me back a year. There were other German kids in the school, but they all seemed to have mastered English already. My brother, Wendel, taught me how to say ‘May I leave the room please?’ and that is all I knew when I went in. I stayed in the first grade for two years because it took me so long to learn English. No one spoke English in my home. My mother never did learn it and my father knew only a few words.”

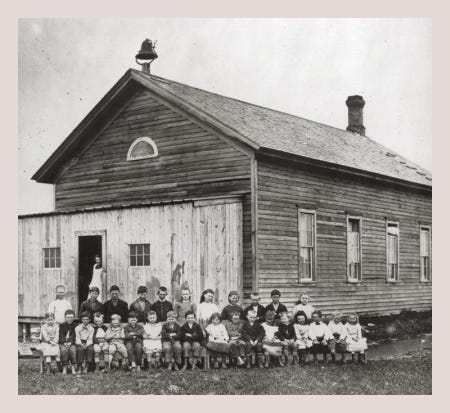

When North Dakota achieved statehood in 1889, there were public elementary schools, but no public high schools, and though the state had a system for certifying teachers, most teachers were, in fact, young girls with little education or experience themselves.

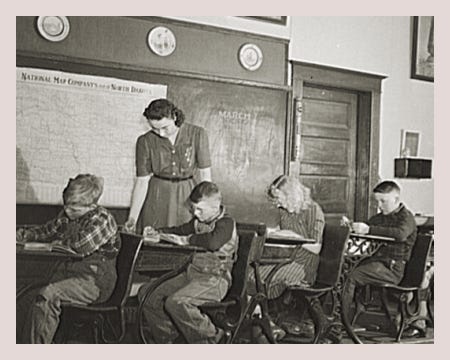

The school districts eventually demanded advanced education for teachers and by the end of the 1920s, nearly all teachers had at least a high school diploma. School enrollment, grade 1 through 8, reached a high point in 1923 with 176,000 students across the state. But few of those students went on to high school and even fewer went to college. More girls completed high school than boys , a fact which reflected boys’ greater value as farm laborers and the broader opportunities for work in cities.

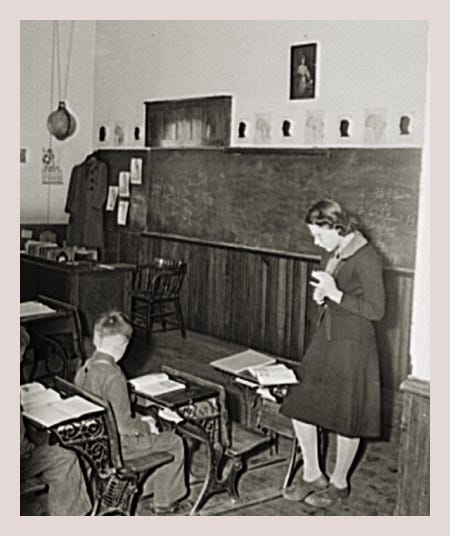

“Cora Norrin was my 4th grade teacher. She always put her arm around me and said, ‘You can do it, Katy!” She was the only teacher who saw me as a real person. She made sure I wasn’t left out. She was the kindest person I ever knew, and now I get teary eyed to remember her. She was so lovely and I adored her because she cared about me. She taught first through fourth grades downstairs and her sister taught 5th through 8th upstairs. There was only one classroom on each floor, and the seats were lined up with a different grade in each row. There weren’t that many students and many were taken out of school a lot because they were needed to work on the farms. Parents thought that was more important than school.

Most of the older boys – the seventh and eighth graders, were expelled from school because they were so bad. They were bigger than the young women teachers, and were rude and unruly. They disrupted everything. My two older brothers were kicked out in the seventh grade and weren’t allowed back. The teachers were not well-paid, and they had to live with whatever farm family had an extra room and would take them in.”

The school situation became quite bleak in the early 1930s when the Great Depression led to reduced property tax collections (which support schools), and teachers’ salaries had to be reduced. Rural schools lost necessary funding and underwent a period of consolidation to reduce the cost of building maintenance, teachers’ salaries, and other school expenses. The Depression left North Dakota schools with a teacher shortage that forced school districts to hire poorly prepared teachers for many more years.

“I looked forward to going to school every day. I was always friendly and wanted to get to know people and see how they lived. I was bullied a lot by other students and had some pretty mean teachers, but I still wanted to go. I couldn’t see too well, and they always made me sit at the back of the room. Finally, I got some glasses when I was 12. They were ugly, round things, but they sure did help. The teacher let me come up front to see the board better now and then, but no one wanted to share a seat with me. I don’t know why, really. Maybe because I had such awful clothes and my hair was just chopped off. Maybe I smelled bad. We did eat a lot of garlic. They called all the Schloss kids “Garlic-eating Roosians” because my parents were Germans born in Russia. They didn’t like us much. Our English was poor and we sort of didn’t fit in I guess.”

“We had a Giant Strike on the playground– which was a tall pole with a bunch of chains hanging down, kind of like a Maypole. Kids would grab on to a ring at the end of a chain and start running really fast around the pole. When we lifted our feet we would all go flying in the air around the pole. Well, I loved that thing, and other kids were always pushing me off of it. I didn’t cry though, I fought back and just swore at them, using every dirty word I could think of in German. The other German kids understood the words, and they tattled on me , “Katy’s out there on the playground swearing at us.” And oh, goodness, I really got into trouble. Later, though, they discovered that I was a great baseball player and made a lot of home runs. So when they chose up teams, they always chose me first. Which was funny because most of the time they made fun of me and teased me and made me so goddamn mad.”

“Miss Makins, the 5th grade teacher, was really hard on me. I don’t know why. She used to call me stupid and she would hit me on the palms of my hands with a piece of rubber hose or with a wooden ruler. Man, that hurt! She seemed to enjoy it. I never understood why someone would become a teacher if they hated kids so much. One time she caught me chewing gum and she made me stick it on the end of my nose and she paraded me around the school as a bad example. The whole school laughed. I was fuming, but what could I do?

“Mr Doyle the 6th grade teacher gave me a whipping with a paddle in front of the other students for swearing in German. He hated kids, too. But he couldn’t stop me learning. I got the second highest score in the county that year – a 98 in physiology. My friend Beulah got 99. I wanted so much to win, but I was happy for her.”

“I liked school and I really wanted to stay, but the rural school ended at the 8th grade. The high school was in town and I was not allowed to go into town. Dad wouldn’t have it. I was needed at home to work, he said. Then I wanted to take a correspondence course. It was the same as high school but you studied and worked on your own time, then you mailed your lessons in. That lasted for three or four months. Then Dad said it was too expensive and that was that.

In addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic, and, within its limitations, history, literature, and science, Katy learned the most necessary skills for her young life — how to survive in an often hostile world. Bullies, unenlightened teachers, a lack of English, poor eyesight, missing parental support — nothing could quell Katy’s tenacity and enthusiasm for learning. And that included braving deep snows during the winters just to get there! (For my previous story about the challenges of a North Dakota winter, click HERE .) Katy remained an avid reader all through her 90s.

Note: The fine old school photos here are courtesy of North Dakota Historical Society.

I have records that date back to the mid 1700s. They lived in Meisenbach, and one lived in Welsebach Rhein, Baiern Germany. They migrated to the US in 1837 and eventually settled in Indiana around Ft. Wayne. For a while I was really interested in genealogy but got away from it . . .maybe a project for the future.

What a history and relatively not that long ago. Thank you for telling her story. When we kids were young and said we were bored, my grandmother had a German saying that translated to stand on your head and catch flies with your ass.

Otherwise she and my mother would converse in German when they did not want us to know what they were talking about.