The direct quotes in this story are from a taped interview of Katy when she was 75 years old. The tape and transcript of her voice is a priceless family treasure.

North Dakota 1920s

The children could hear him coming down the dirt road in his big Chrysler Imperial. He had one of those loud horns that said “Aaooooga! Aaaaoooooga!”, and he started honking over a mile away. The little ones would get so excited they’d run to the door and practically dance a jig. “Uncle Georg is coming! Uncle Georg is here!” Every couple of weeks Uncle Georg would drive out to the Schloss farm from his home in the neighboring town of Harvey. He loved those kids and treated them with such kindness. He always brought a whole baloney and a couple of loaves of store-bought sliced white bread. He didn’t care what time of day it was, he went right into the kitchen and made a bunch of thick-sliced baloney sandwiches. He let the children eat until every crumb was gone, and they thought it was the best food they’d ever tasted in their little lives.

The children at the farm were worked hard, they were not catered to by their stern parents. Katy and her brothers were seldom given treats, and the times that they were allowed to just play and have fun were far between. Their mom and dad probably didn’t approve of that baloney business, but they never said anything about it because Uncle Georg was the man who had sponsored their immigration to America, and who had loaned them the money to buy the farm. Uncle Georg could pretty much do whatever he wanted there, and what he wanted most was to give those children a treat.

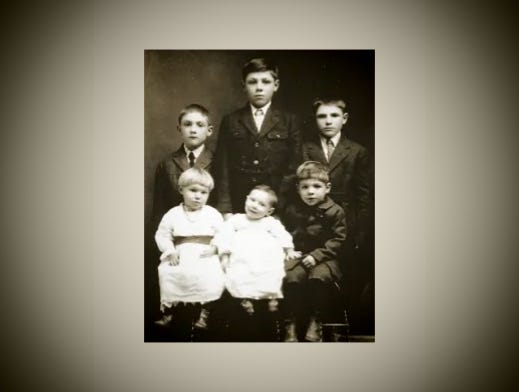

Katy’s ancestors were dour Catholic German farmers who had lived in Ukraine for more than four generations; her parents left Russia in 1912. She had three older brothers who were somewhat feral – boorish and un-schooled, always in trouble. She had two younger brothers who were bewildered, shy red-headed boys who just did what they were told and tried to keep out of harm’s way. Katy, the one girl, was valued, apparently, only for as much as she could work with her mother and wait upon the older males in the family.

“I earned my keep from the time I was four. I was old enough to go out and shake the rag rugs and sweep up the shells of the sunflower seeds that the men spit on the floor. As I got a little older, I carried in buckets of water from the pump, milked the cows, fed the animals. I dug up the beets, peeled potatoes, you know, stuff like that. My mama taught me how to sew and mend, not fancy sewing – just a lot of ordinary woman’s stuff. But, you know, she never taught me to put cold water in the mush pot and let it sit a while so it would be easy to clean. No, I just scrubbed and scraped away at that old dried-on mush with my little fingers. I was so mad when I found out the secret of soaking it first. Why didn’t she teach me that? Another job I had was cleaning the threshold. I remember how I had to scrub those boards with a brush and Clorox so it was bleached white. Boy, I’ll tell you, my mama kept a clean house! I did a lot of the cleaning, a lot of housework from the time I was just little.”

One of young Katy’s major contributions to the running of the farm was tending to all the animals. Her younger brothers would help.

“We had a regular old farm with all the animals. We had draft horses, milk cows, pigs, chickens, dogs and cats, and everything. It was a lot of work every day to tend to the animals, they all had to be fed. The horses got little buckets of oats every day and we threw lots of hay in the manger. I loved the little piglets. They would eat any left-over food scraps and peelings. There wasn’t much waste, I’ll tell you. We used up everything. Those pigs loved to chew on the corn cobs, but we also used the dried corn cobs to kindle the fire in the stove every morning. Our cats were not pets, they took care of the mice in the barn, but our dogs didn’t do anything, they were not working dogs. I guess they barked when someone came around, but mostly they just slept under the porch”

Katy’s family, like most of the North Dakota farm families, raised and preserved most of their own food. In addition to acres and acres of durum wheat, they maintained a large kitchen garden with the vegetables Germans like best, such as cabbage, potatoes, beets, onions, cucumbers, pumpkins. Katy and her mother canned or pickled them to last all year long. Long rows of dusty glass jars lined the walls of the cellar. They also had a field of oats and corn to feed their animals. I remember huge cotton sacks of home grown sunflower seeds in one of the bedroom closets and barrels of dill pickles in the cellar that were so hot from all the garlic and pepper corns, my lips were on fire before I could finish one.

“Starting when I was about, I don’t know, maybe about eight, I learned to cook for everybody. I stood on a stool at the stove. We ate a lot of potatoes and dumplings and noodles because we were Germans. We made the noodles with eggs and flour from the farm. Dampfknudel, knopfel, Eiernudel – that’s the wide, flat egg noodles. All kinds of noodles. When Mama was too tired to roll out the dough for noodles, she made something she called rivola, but I think other people call it spaetzle. She would just pinch off little bits of dough and drop them into the boiling broth. Sometimes we made something called blachinda, which was like a little turnover with pumpkin in it - not sweet like pumpkin pie, more like squash. Oh, that was so good!

We grew all our vegetables, and we raised a few pigs for their meat and for lard. There wasn’t a thing called shortening then, just lard. We had cows for our milk and butter, but we separated the cream. We put the cream into tall milk cans, and every Saturday evening we all went to town and sold the soured cream, in order to buy other things we needed, like coffee and sugar, and yeast and baking powder and vinegar.”

Sometimes when the parents would go off visiting neighbors on a Sunday, and the older brothers were out running around, getting into trouble, Katy and the two younger brothers were left alone. They would go out to the barn and steal some of the forbidden cream from the cream cans. Brother Johann would open up some home-canned tomatoes and add milk and the stolen cream to make a great soup.

One time when the three youngest were left alone, they went outside and experimented with making a little fire. “We knew it was mischief, but we were just bored and didn’t think,” she told us. They accidentally set the entire haystack alight – all the hay that was needed to keep the animals alive through the winter. When their father returned and saw what they had done, he was so enraged he beat them mercilessly.

“He would have killed all three of us, if our Uncle Georg had not stepped in and stopped him. He was so desperate, he didn’t know what he was going to do, but you see he had good neighbors and they came from all over and donated shares of their own hay, so that he had enough to get by.

Oh well, we didn’t get into too much trouble. There wasn’t time for it. I worked hard when I was a kid, same as my brothers did, from sun up to sun down, but it was normal, and the only life I knew. Everybody had to work. Dad and the boys worked in the wheat fields, mama and I worked in the garden, cooked and canned and cleaned all day long. She liked to crochet in the evening. I just went to bed, I was tired I guess.”

The arduous life of my Russian-German family, was, no doubt, no different from any of the farming families in the early 20th century. It was hard on a little girl, but the practical skills Katy learned on the farm, and the hardships she had to endure at the hands of her wild brothers, her unresponsive mother and ill-tempered father, gave our Katy strength and courage, and prepared her well for the vagaries of life she was to encounter when she left North Dakota behind at age 16.

Well done, Sharron! Keep sharing your family’s history.

Wow. Just wow.