This little story is dedicated to Marina Gatti, who encourages me to write.

She was sitting in her armchair in a daze one March morning. My mother was ninety-five and spent quite a lot of her days then, moving in and out of lucidity (as we all do at times), some days more, some days less. She had lived with me for sixteen years and I noticed she was beginning to fail, very slowly at first, and then more rapidly. She was not diagnosed with dementia, she was not ill, she was just old and beginning to shut down, piece by piece. It began with small things like forgetting to brush her teeth, or only wanting to eat ice cream, or not wanting to leave the house.

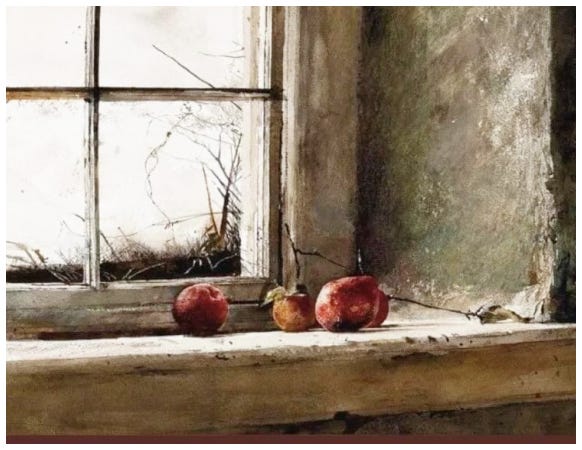

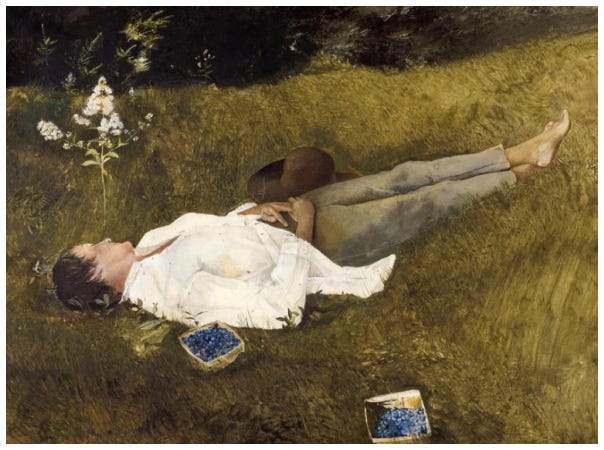

She had her favorite book on her lap that March morning, a large picture book of Andrew Wyeth’s paintings. She loved his work. She said she could “read” the pictures, that each picture had a story, and no words were necessary. She often told me her made up stories about his paintings. But one picture was puzzling to her. It was titled Trodden Weeds.

“Now, look at this one,” she said. “I have been trying to figure out this picture. Who do you think that man is? Where is he going? Why is he wearing those big old knee boots?”

I told her I didn’t know the story, but that I would find out. I began writing that evening, just one paragraph.

“…. He looked at his reflection briefly in the old mirror hanging near the kitchen door. For want of a comb, he wet his hand at the faucet and smoothed down the mouse-brown hair on top of his head. He whacked his hat against his thigh a couple of times, sending the dust flying, and put it on his head. Stepping out onto the sagging porch, he surprised three morning crows in the empty yard. They barked the usual insults at him and hopped over to the trough as he walked by.”

When I awoke in the morning, his name was rattling around in my head. It had come to me in a dream. Bartle Clunes. I got my morning coffee, sat down in a sunny window and wrote two more paragraphs. In the afternoon, I told mama I was writing about her mystery picture. I read to her what I had so far. She settled back with the picture-book open on her lap.

“Setting out across the barren fields, Bartle Clunes, could sense the subtle changing of the season, he felt snow coming. The sky was clear, the air had a sharp bite and a dampness to it, the frosted stubble of grass crunched under his tread. The tops of his tall worn boots flapped against his knees as he walked. He pulled his handkerchief out of his pocket and blew his nose.

“Buttoning the collar of his dark wool coat against the late October chill, Bartle was heading over to the sunnier side of the draw to see Louvina McBean. He was either going to ask her to marry him or he was going to buy one of her dogs. He hadn't decided which. The only thing he did know was that he was done living alone.”

I wrote a little every day, and read to her. Sometimes I would read to her in the morning and by the afternoon she would have forgotten and would ask me, “What is old Bartle up to today?” And I would read it again. After a few months, (and forty-five chapters later), she came to think of Bartle as a friend. The foothills landscape in which he lived was real to her. The story invited us both into a small rural settlement in the year 1949, where we met diverse residents of California’s gold country. She knew the names of all the characters and talked of them as if they were her neighbors, and, I guess, in a way, they were.

I did not write the story with publishing it in mind; it was for my mom. Oh, I can write readable stories, but I have no pretensions of having the talent or the stamina or the temerity it takes to sell a manuscript. Although this story was the perfect vehicle for my mother and me to spend meaningful time together in the last months of her life.

We had long talks about the life in Riles Crossing. She loved that the story line was uncomplicated, there was no meanness, and very little sadness in their world. They all got along and helped each other. She recognized that the language used was the rural language of her generation in 1949. She remembered the colorful idioms and the polite, rather formal language that people used in those days. I heard my grandmother speaking to me in the dialog.

Without any preconception, Bartle Clunes became a tale of rescue and redemption, of finding room in one’s life for the most unlikely people. It turned out to be a joyful testament to the transformative power of friendship and love, and how it may change one’s life and the lives of an entire community. And it made a difference in my mama’s end days, I am sure of it.

As it turns out, over two hundred people have read Bartle Clunes on Substack and in paperback since my mothers death. I could not be more delighted. Let me shamelessly suggest that if you have a friend or family member in their older years, share Bartle Clunes online with them. It would be a sweet gift. It is free and is presented chapter by chapter. And if you are a caregiver for an elderly person, they might even like you to read it to them.

The Bartle Archive is HERE .

So that is where the story comes from. It is wonderful that you were able to share the story with your mother. It must be like a memorial to her for you.

So very poignant Sharron. A very dignified tribute to Katy. Thank you for sharing this.